Here are just a few photos of my exhibition in Crate Margate.

It was great to see people enjoying the pictures and I enjoyed the three days. I hope to show the work again in the future.

Here are just a few photos of my exhibition in Crate Margate.

It was great to see people enjoying the pictures and I enjoyed the three days. I hope to show the work again in the future.

I’ve very pleased to say that I’ll be exhibition my work in the Crate gallery in Margate. Please come if you are in the area. I will be posting images and video from the set up and open days on Instagram @miriamcomber.

“Our Messy Emotions vs Automated Empathy” will a free exhibition at Crate from 7th to 9th June 2025.

Open :7th June 4pm to 7pm, 8th and 9th June 11am to 4pm.

Location: Crate, 1 Bilton Square, High Street, Margate, CT9, 1EEFor more information, please visit cratespace.co.uk

Jessa Fairbrother is an artist working with embroidery on self-portraits. Her work is exceptional, very beautiful, very delicate and very emotional. I strongly recommend you have a look at her website and Instagram @jessfairbrother.

While her work is a world away from mine, I felt we have common ground in stitching meaning into photographs. Jessa runs workshops in her studio in Bristol and we organised a day that would be part portfolio review and part workshop.

It was great to do a portfolio review face to face. I brought all my embroidered images, pinned on foam board, with a selection of glass beads, so I could re-create the total effect, and A5 prints of the final images. Jessa put together groups of images that worked well together. I’m always interested in people’s view on this because I think I get blind to the images after working on them so long. For example, one of the things that never occurred to me was that the shoulders should be in about the same place in sets, so they look good together.

We also discussed developing the work. One thing that we tried was using just one type of glass on several images. I include glass to refer to the internet, but it’s a stretch for viewers to make and keeping the expression of that idea constant could help.

The conversation about the images always came back to the ‘why’ being the project. What am I trying to say, why am I making these choices and, of course, why does it matter? This informed a conversation about what the final image is and the difference between a unique image, which Fairbrother makes, and a collage, which is what I make. I’d not thought about the images being collages.

Jessa is an expert needlewoman and, although I’ve some experience with stitching, she was able to help me get a better understanding of the technicalities of sewing on photographic paper – the best paper, thread and needles to use and how to start and finish off. I found I had a lot to learn. For example, while I use good quality paper, I’ve used any old adhesive (to stick on beads) and tape (to keep tension the thread) . I now understand that I need to think about using materials that are acid free and won’t rust even if the work is not going to be the final image.

An added bonus was seeing Jessa’s work and her talking me through the techniques and the thoughts and inspirations behind each. The work stretched back to a piece from her early work “Conversations with my mother” made after her mother had died and she found that she could not have children herself. Across a number of works she explained how she uses thread and perforations of the image not just as decoration but as metaphor for attachment, absence and more. Her work is highly decorated, but I’d not understood until I saw the actual objects that the stitches are very small and delicate. The stitches used not complex, but the patterns are intricate and interesting. Of course, one of the key points of doing this kind of work is that there is a sort of jeopardy – mistakes cannot really be corrected.

This was a really useful and enjoyable day. I got:

Beyond all this our conversation gave me a really interesting and useful insight into what an artistic practice means and the context of the art industry. As well as a font of knowledge, Jessa is a lovely person to meet.

Doing a New Year tidy up on old files and folders, I came across these images. They are about Digital Identity and look at the idea that, since AI is prone to errors and biases, our digital identity likely includes errors and is constructed with biases built in.

I took a digital self portrait, printed it and cut the print into squares, deconstructing the whole into items of information. I then used these squares to reconstruct my identity, but with errors.

The titles refer to what has happened to the information in reconstruction.

While all the images are digital, the deconstruction and reconstruction are purposefully manual, which introduces its own irregularities and errors. This is a reminder that, for the moment at least, humans make AI and it is as imperfect as we are.

For all its problems, I still like this work. I saw something similar recently but with jigsaw pieces, that looked much better. Rather like the embroidery work, there was something meditative about the slow process of putting the squares together – I used a scanner so all the squares were face down. I couldn’t actually see what I was doing and they moved at the slightest touch!

I was reminded of a talk by Milo Keller’s (Contemporary Photography and Technology) where he suggested that the point of producing objects is to slow down the hyper speed and hyper production of digital photography. This process does produce a digital image, but in a slow and reflective process.

Keller, Milo (2020) Contemporary Photography and technology. A Vimeo recording of a lecture from Self Publish, Be Happy, September 10th 2020 http://selfpublishbehappy.com/2020/05/online-masterclasses/ [Accessed 17th January 2021 – pay to rent]

I’m very pleased to be taking part in this large group exhibition, along with several of my OCA colleagues. It runs from 27/11/2023 to 02/02/2024 in Cambridge.

https://shutterhub.org.uk/shutter-hub-open-23-24-selected-photographers-announced

I’ve very pleased to say that I’ll be exhibition my work in the Crate gallery in Margate. Please come if you are in the area. I will be posting images and video from the set up and open days on Instagram @miriamcomber.

“Our Messy Emotions vs Automated Empathy” will a free exhibition at Crate from 7th to 9th June 2025.

Open :7th June 4pm to 7pm, 8th and 9th June 11am to 4pm.

Location: Crate, 1 Bilton Square, High Street, Margate, CT9, 1EEFor more information, please visit cratespace.co.uk

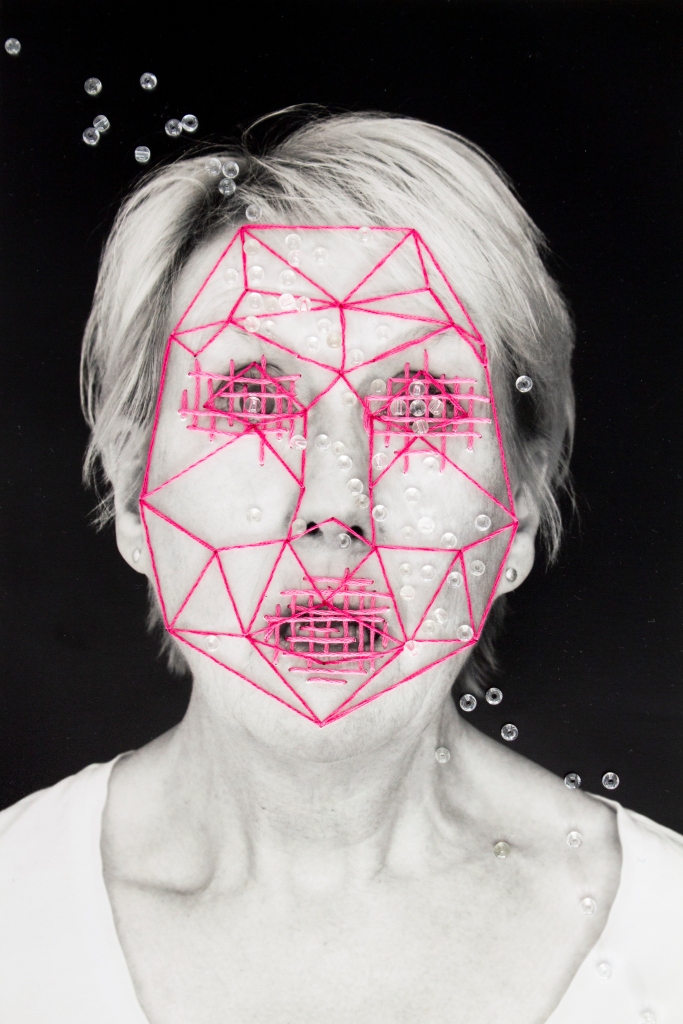

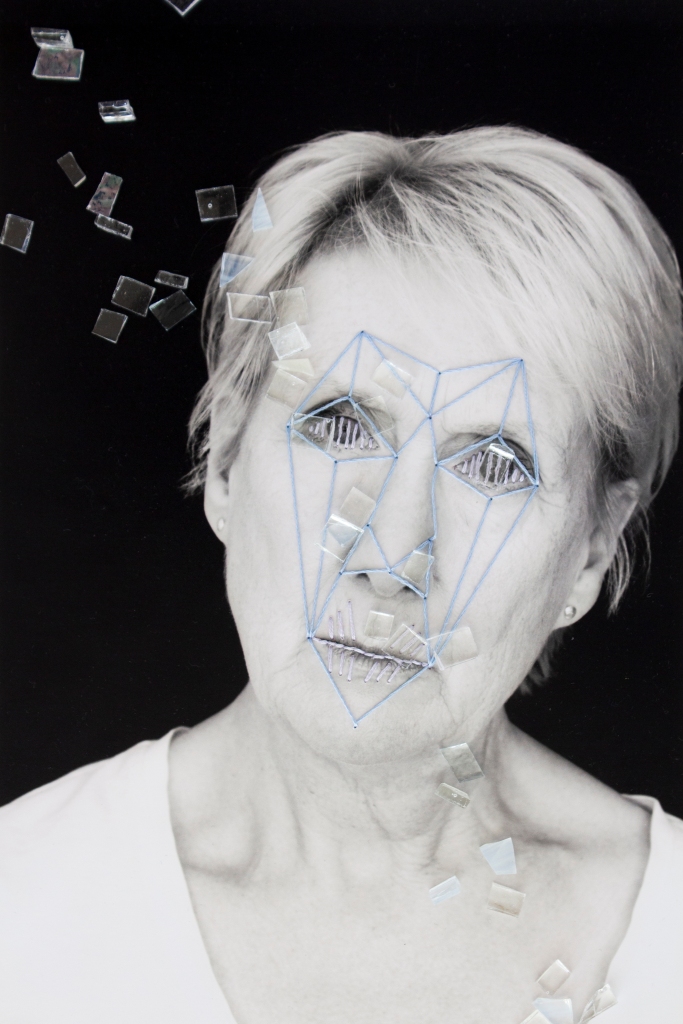

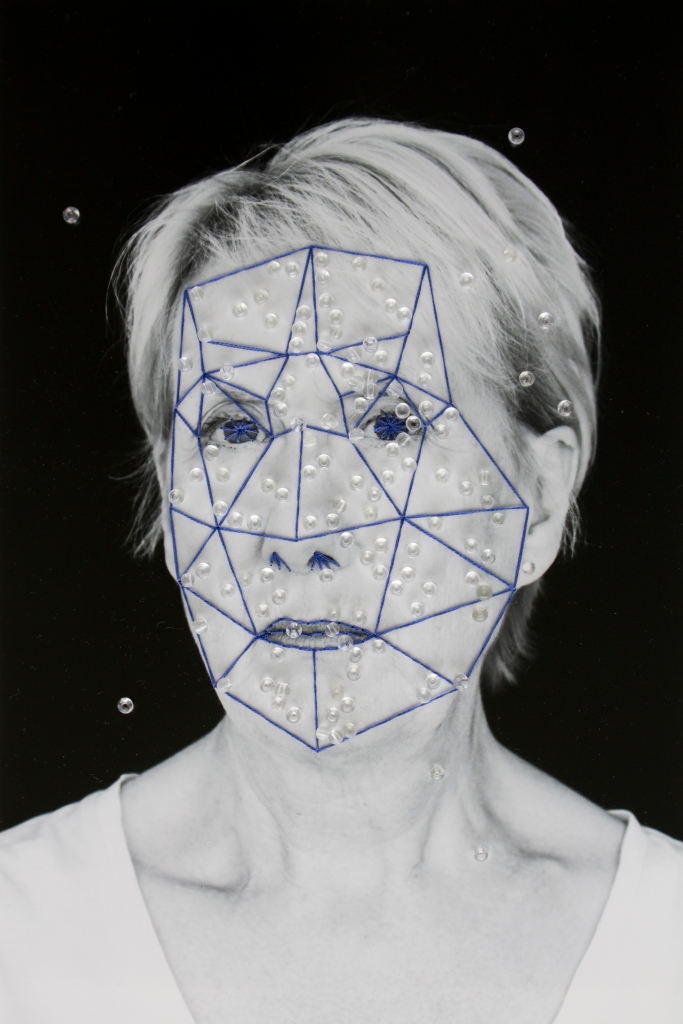

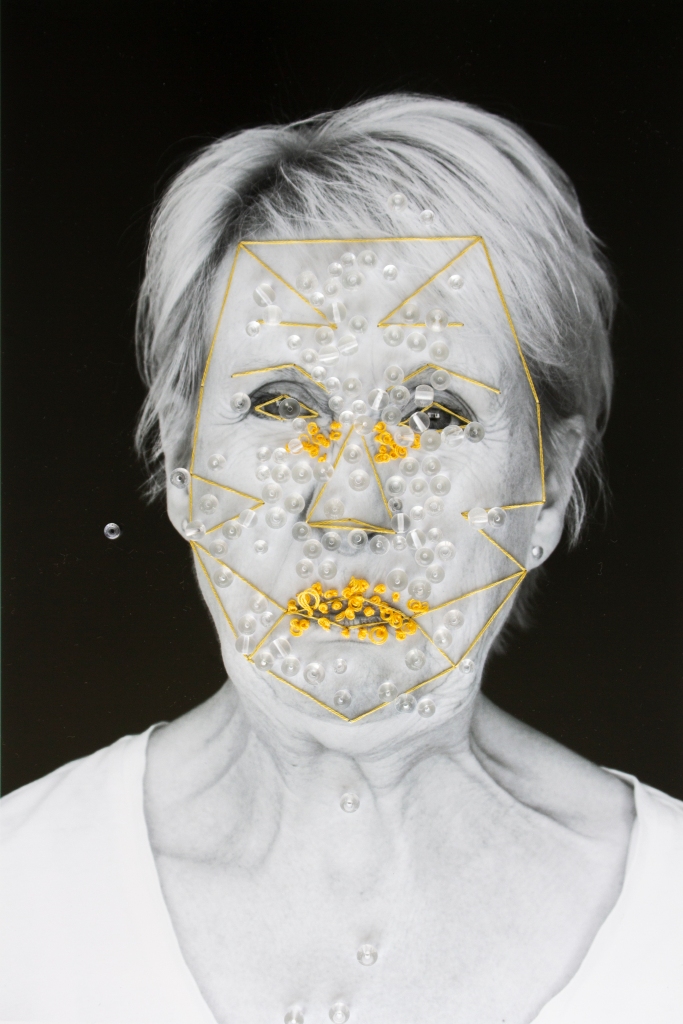

You probably know that AI can be used to identify our faces. It is also used identify emotions, based on our facial expressions. This is even more problematic. The Emotion AI (EAI) models tend to assume that we all experience the same limited range of emotions – rather like the idea of five emotions in Disney’s Inside Out – and express them in more or less the same way.

Our emotions are more complex than this. and we express them in different ways depending on context – we have different smiles when we’re happy and when we’re being polite; we cry about sad events and sad films. But we know and understand these differences.

EAI is flawed and simplistic, yet it is offered as solution to, for example, choosing suitable candidates for jobs, measuring the engagement of students and measuring customer satisfaction.

This series expresses my scepticism that EAI can clearly read and understand emotion and my resistance to its intrusion. I want to reject the possibility that what we feel can, and will, be categorised by EAI; that a program might catch my expression and decide I need to cheer up, calm down or would like to buy something.

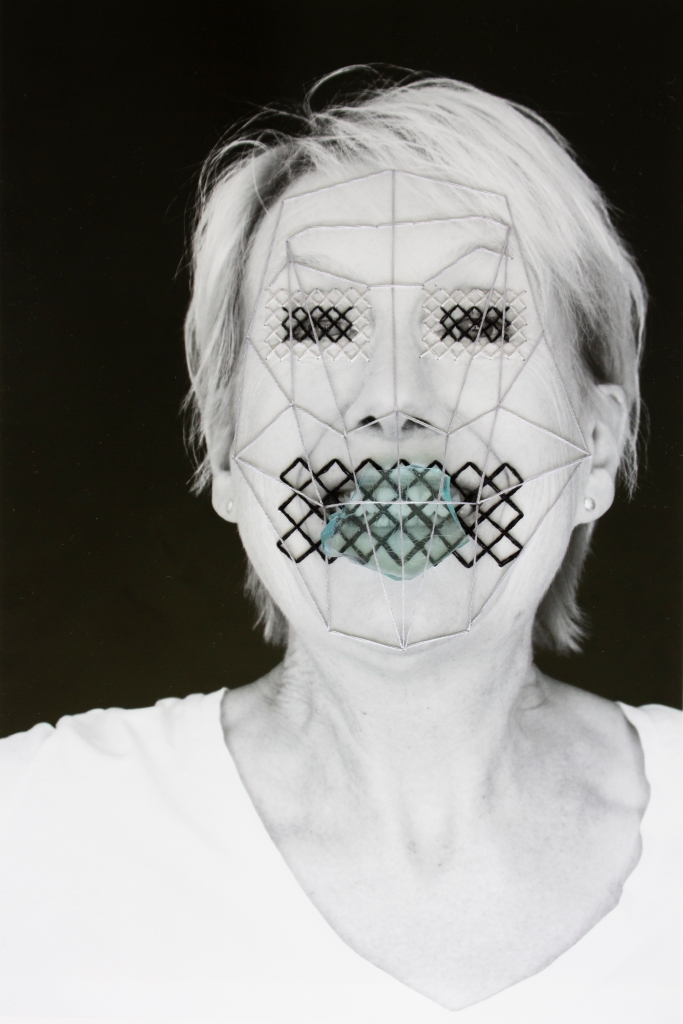

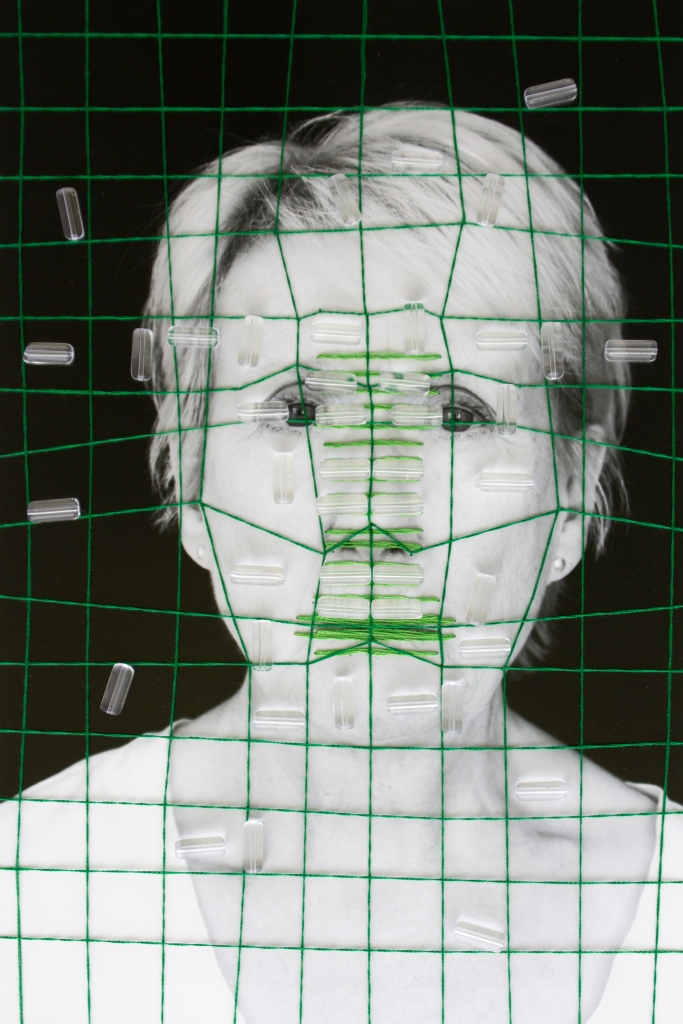

Each self-portrait shows me expressing an emotion. I take a B&W print of the portrait and add embroidery and other stitching to hide that emotion. I also add pins and linking threads making a ‘net’ to mimic how Emotion AI might take a reading from the face. I use stitching so that the solution to being decoded is based on craft, which is more a more human approach than tech.grounded in handiwork and tradition, and so a more. Finally, the addition of glass is about the way we are seen and see ourselves – through the screens, lenses and optic fibres of the Internet.

We are living in a culture of digital surveillance. This is not something that is imposed on us. In fact we are active or passive participants.

We are immersed in surveillance through the networked devices that have become an essential part of our everyday life. Every interaction with these devices produces data – what we type, what we like, what we look at and for how long. This data is why we don’t pay for the internet in money. Instead, we give tech companies this data for free and they run algorithms so they can use the data to make money. We know that what we search for, like or share will shape what we are shown and assumptions about what we want to buy. Everything is data. Where we go, how we get there and how long it takes us is played back to us in digital maps. What we buy, cook, eat and when is all data. Even our health, from our step count, or the timing of our periods to doctors’ records, is data.

Photography contributes to the mass of data captured. Our face is scanned to identify us at airports, but also buy our phones and laptops. Smart devices like doorbells, cars and vacuum cleaners collect video. Our image, particularly that of our face, can be thought of as a special kind of data. It not only represents our identity but also provides a window to our inner state, a window that can be used to classify, and potentially commoditise, our emotions.

Emotion need no longer be a human sense of vague, indefinable “feelings,” instead emotion is in the process of becoming a “legible,” standardized commodity (Scott 1999) that can be sold, managed, and altered to suit the needs of those in power.

Sivek (2018) p2

Sivek, S. C. (2018) ‘Ubiquitous Emotion Analytics and How We Feel Today’ In: Daubs, M. S. and Manzerolle, V. R. (eds.) Mobile and ubiquitous media: Critical and international perspectives,. New York: Peter Lang. pp.287–301.

The starting point for Emotional AI is the work of Paul Ekman. Ekman was inspired by Charles Darwin, who wrote about the universality of emotions. He was also inspired by Duchenne de Boulogne, the French Neurologist best known for his grotesque photographs of people with their faces contorted into grimaces by the application of electrical current. Duchenne was interested in physiognomy – the relationship between our physical being and our internal being. Ekman was interested in the idea that our faces could show a specific range of emotions. He also worked with an isolated tribe in New Guinea to gain evidence that emotions are universal.

Ekman identified six universal emotions: fear, anger, joy, sadness, disgust, and surprise. These have been used for a number of Emotional AI models including by Affectiva, one of the largest Emotion AI companies, now a subsidiary of a vison tech company, Smart Eye.

This is not the only model used. For example, some tools also label data based on the intensity or valence of the emotion. Some researchers also use more than the face, for example, looking at gait. It is also true that the underlying models will be improving over time.

According to an article by (Dupré et al., 2020) the answer is “no”. Or, as we should say with a developing field, it was “no” in 2020. Dupré et al tested eight different commercially available classifiers and none was as good as a group of humans. Classifiers were better at identifying simulated emotions, but still not as good as humans. This could well be because simulated emotions may be over-acted (see images below).

The Dupré et al article gives a very good summary of the problems with classifying emotions:

Here are stills of video image used in ADFES – a data set of images used to test models of emotion produced by the Amsterdam Interdisciplinary Centre for Emotion (AICE) at the University of Amsterdam.

To my eye these look poorly acted. The first and second expressions, starting from the left, are pretty strange. Little wonder that models trained on images like these struggle to identify emotions.

“MorphCast Interactive Video Platform can offer benefits to:

Affectiva Media Analytics

Ekman, P. ( 2007). The directed facial action task. In J. A. Coan and J. J. B. Allen (Eds.), Handbook of Emotion Elicitation and Assessment (pp. 47-53). Oxford University Press.

Ekman, P., & Friesen, W. V., & Hager, J. C. (2002). Facial action coding system: The manual on CD-ROM. Instructor’s Guide. Salt Lake City: Network Information Research Co.

Dupré, D. et al. (2020) ‘A performance comparison of eight commercially available automatic classifiers for facial affect recognition’ In: PloS one 15 (4) p.e0231968.

Your smartphone can probably recognise your face. We know that electronic passport gates can also do this and we often see AI using CCTV footage to identify people in fictional dramas. Emotional AI (EAI) goes one step further, capturing and decoding our facial expressions to measure what we feel. So, how do we feel about our phones checking what mood we’re in? Or any other device with a camera for that matter?

EAI was originally developed for health-related applications. For example it was trialled as a way to help people who had difficulty understanding the emotions of others. But now the main uses are commercial (Sivek, 2018). These include solutions to tell employers whether their workers are concentrating[1], to help researchers “accurately and authentically understand the emotional response” of interviewees[2], to collect objective data on job candidates[3]. As with many AI applications, EAI captures data (our expressions), classifies it using comparison to a training set and using standardised categories or variables and outputs it’s best estimate of the emotions we are feeling.

There are legitimate concerns about EAI.

All of this is fairly typical of AI. First, there is an assumption is that quantity of data trumps theory. Second, there is a tendency to ‘satisfice’ – to choose to aim for answers that are good enough rather than being completely accurate.

The best summary I have seen is by McStay (2018) who, to paraphrase, says that EAI replaces an understanding of emotions as ambiguous, bound up with context and culture, with a system that gives a ‘veneer of certainty’ about their classification.

So, we are left in the situation that EAI is not terribly accurate, so we probably don’t want it being used to measure our emotional life. But, on the other hand, if the model do get more accurate, would we really want AI models looking beyond our face and into our inner life?

[1] Fujitsu Laboratories Ltd Press release: Fujitsu Develops AI Model to Deterimine Concentration During Tasks Based on Facial Expression Accessed 29/05/2023.

[2] Information from the Affectiva website. https://www.affectiva.com Accessed 27th May 2023

[3] Information from the MorphCase website, https://www.morphcast.com Accessed 27th May 2023